The True Value of a Tight End

As the connective tissue of the offense, Tight Ends are often most needed where they're least visible

The brand of defensive football that dominated the 2010s has created a lot of lingering misperceptions about what offenses can get away with. Without getting too academic, the Legion of Boom convinced the entire league that loaded boxes and Cover-3 are the foundations of defense, and are to be played a majority of the time no matter what. The L.O.B. dominated within this framework due to their uniquely good teaching and of course, collection of players who happened to all have the skillsets for it

For the rest of the league, this led to an explosion in passing. Traditionally, these favorable passing looks are the benefit of a punishing run game, but with defenses presenting them no matter what, running the ball well became pretty insignificant. This bubble happened at the same time analytics began to flourish, which created the idea that running the ball doesn’t matter, and play action works the same whether you run it well or not. For a window of time, this was completely true. This allowed offenses to, during that brief flash in NFL history, operate under the schematic equivalent of eating candy for every meal or making money without assuming financial risk. Teams could spread out and pass as much as they wanted because defenses kept *themselves* honest. This changed the Tight End position considerably. There have always been receiving-first guys at the position, Shannon Sharpe comes to mind, but offenses began to live league-wide in 11 personnel (3 WR, 1 TE, 1 RB) for the first time.

Normally in 11, the TE has to be a serious blocker, at least of course outside of obvious pass situations. If he isn’t somebody who does a lot of blocking on the line, you’re basically in 4 WR. During this era, that didn’t have any consequences. The Chiefs were the best example of how devastating these offenses could get, for all intents and purposes running the NFL’s first true air-raid. They only had 5 credible run blockers on the field. Because defenses were keeping themselves honest, the Chiefs didn’t require any more than that. They could max out with weapons and bomb you. Many offenses followed suit and the NFL saw passing numbers it had never seen. It got to a point where people wondered if good defense was even still possible. It looked like the NFL would become like the NBA, where you can only hope to slow scoring a little because of all the space, rather than dictating to the offense.

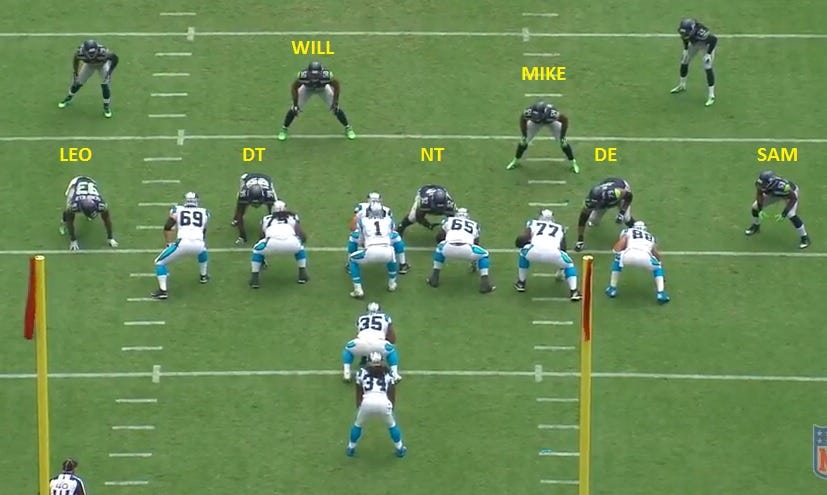

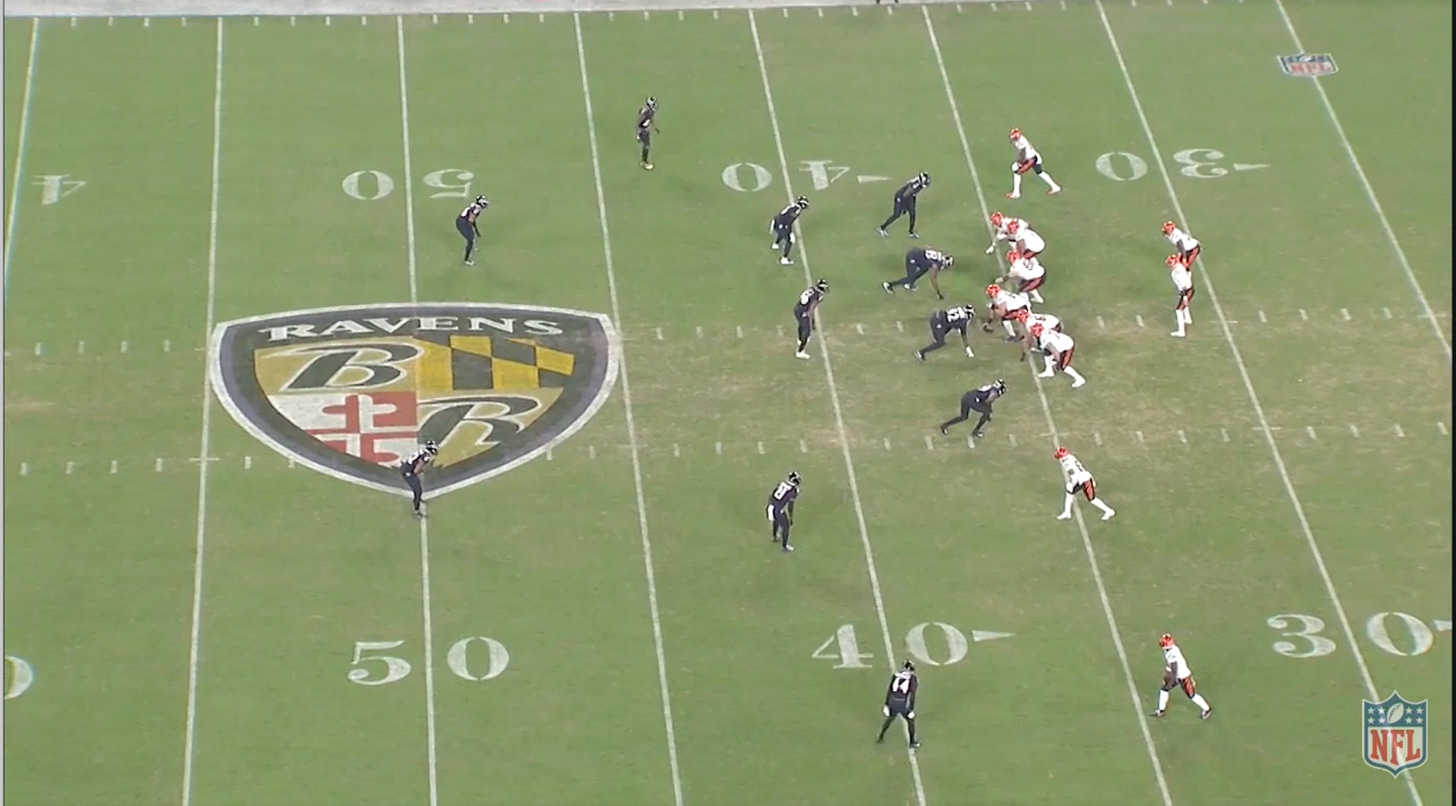

Well, the jig is up. Something happened in the league around 2021. Patrick Mahomes’ average depth of target, which sat at a robust 8.4 yards in 2020, plummeted a full yard to 7.3 a year later. NFL defenses are no longer made in the image of Pete Carroll, but Vic Fangio. You’ve heard a lot of discourse about “2-high defense,” and for good reason. It’s been discussed a million times, but the meta of defense has completely flipped. The main objective of defense, understandably, has become the elimination of space rather than presence in the box. In the postseason that year, the Cincinnati Bengals decided they didn’t have to be honest against KC, emptying the box and dropping 8 into coverage over and over and over. Mahomes got impatient with checking the ball down for 4 yards and malfunctioned in the 2nd half, allowing the Bengals to come back and steal it. Offenses just weren’t prepared for this shift (with an exception I will get to in a second). The reality now is that offenses unable to condense and punish empty boxes are stagnant and stoppable. It’s now easy for defenses to take away space and force them underneath over and over and over. For spread-only offenses, it’s incredibly difficult to generate explosive plays and throw downfield. The pendulum at one point had swung so far in the opposite direction that people called for 2-high structures to be BANNED for the entertainment product of the league.

Even teams like the Bengals (who have, as a result, since made major changes at TE), with the most explosive QB/WR combo in the league, have struggled to get the ball downfield because they can’t force defenses to load the box and stop selling out against their vertical passing game. In 2022, they played 11 personnel on 82% of snaps (the league average was 60.1%) and threw the ball 65% of the time. Their TE, Hayden Hurst, wasn’t a strong in-line blocker and their receivers didn’t block in the run game much either. As a result, defenses felt no need to fill the box. The Bengal O was good overall because of its ungodly talent, but it ranked a frustrating 27th in average depth of target, and against defenses like Baltimore and Kansas City, ran into serious situational issues. If the safeties are both free to play deep, they can disguise and get into any coverage they want at any time, as well as being more specialized in what/who they take away. When the box is loaded, coverages are basic, predictable, and vulnerable downfield. Offenses across the league have been impacted by this shift, with the notable exception of that one particular family of coaches branching off a certain 49ers coach. You know, the group that never stopped emphasizing the ground game, that school of offense that now rules the league. Not only did they not notice a thing, all of this probably made their lives easier while it was making everyone else’s harder.

The paradigm shift has restored the traditional reality of what you need Tight Ends for. The value of a Tight End is not that they catch the ball, that’s what Wide Receivers are for, it’s that they’re the only guys who catch the ball *and* block on the line of scrimmage in the run game. They’re the ligaments that connect the different muscles of your offense. The undiscussed reality is that it’s impossible to seriously run the football without Tight Ends who can block. The OL is the main engine of a run game, but the auxiliary blockers (TE, FB, and often WRs) are critical, you cannot do it without them. The TE position is the most important of these. If a TE can’t block, he can’t be the only TE on the field, and if he’s the 2nd TE on the field, he’s taking the spot of a 3rd receiver. I will get more granular in an upcoming piece about exactly how and why this is the case. For now, though, your offense can’t work without a blocking TE, and those who can block in-line and run routes create the most value. With guys like George Kittle or Rob Gronkowski, you don’t always need 2 separate players to achieve this. They create an entirely separate amount of value that is mostly invisible in the box score, but front and center for offensive coordinators. There’s no personnel grouping or down/distance in which George Kittle has to come off the field, but that’s not the case for say, Mark Andrews. If Andrews is on the field in 11 personnel, you don’t have to honor the run all that much. You have to still be exceptional as a pure pass catcher when judged against wide receivers, not other TEs, to fully escape the implications of this reality. I call this threshold “the Wide Receiver Test.” The fact of the matter is that most aren’t. Among TEs this season, the only one who would place in the top 15 among WRs in yards per route run is, ironically, George Kittle at 2.84. After him, there is a drop-off. Trey McBride is next at 2.46, which would be 16th among qualified receivers between Marvin Mims and rookie Brian Thomas Jr (who is held back statistically by a dysfunctional offense). And that’s the 2nd best TE figure! Jonnu Smith, for example, sits 5th at 2.18 which would be 31st among WRs.

As far as offensive personnel deployment goes, let’s take a look at a real-world example of what that looks like. In Buffalo, they have 2 key pass catchers who are best in the slot: Dalton Kincaid and Khalil Shakir.

From a run game perspective, the two are honestly similar in quality and role, as Shakir, like many modern slots, is a physical blocker of Nickels and box Safeties in tight spaces near the formation (shoutout to 13 Mack Hollins here as well). The big difference is found in pass-catching. Kincaid sits at 1.9 yards per route run while Shakir is at 2.65. With limited opportunity cost either way in the run game, which of those guys would you rather have in your primary slot role down to down? Obviously, it doesn’t exist in a vacuum and there are situations where both can be out there, but in general, only one of them can play in the slot in most situations and naturally, one will eat into the other’s snaps a bit. The difference in pass-catching quality isn’t just in the (rather stark) statistical figures. Receivers are faster/more agile and rangier, even pure slot types like Shakir or Amon-Ra St. Brown, and can threaten on a wider array of routes. With all that in mind, in a broad sense, would you rather have Shakir take snaps from Kincaid? Or Kincaid from Shakir?

Tight Ends have to make up the difference in receiving value somewhere, and that’s where the bigger bodies and expanded blocking capability come in. If you’re going to be a diminished receiver, you have to be an expanded blocker to avoid the value/usage proposition of simply being a slow WR. The more value you generate as a blocker, the more you carve out a role that can’t be backfilled by another position. After all, as I said earlier, viable TE play is CRITICAL to the functionality of a running game. The TE’s value is in their ability to lend a hand in every area, allowing the offense to access both run and pass at the same time, from the same looks, because of their presence on the field. With the run game once again essential to attacking defenses, this reality is back at the forefront of the position.

*All statistical figures from Sumer Sports.

Great article! A nuanced question—how frequently do defenses match personnel groupings? The underlying question is whether a TE covered by a LB is a better “pass advantage” than a WR covered by a nickel. This would be impacted by zone/man rules as well.